-

Look Up, Look Out

Phoebe Lemin, Sarah Meeks, and Matthew Merlo

Explore the homes of residents of the Old Eighth Ward, view the photos of Harrisburg from 1890-1920, take walking tours through the city, and encounter the people who impacted the ward.

-

Educational Reform in the Old Eighth Ward: With Biography of William Howard Day Website

Olivia Bardo, Molly Elspas, and Zöe Smith

In the early days of the Old Eighth Ward, education was segregated and the responsibility of church communities. Thomas Dorsey founded a school for “colored children, both free and bound,” in 1817 in the Wesley Union AME Zion church building. Eventually, a three story building, located between the Jennings Foundry and the Wesley Union church, known as “Franklin Hall” became the primary educational home of the Ward’s pupils. However, Franklin Hall was poorly suited for educating children. J. Howard Wert, writing in the Patriot, described the conditions there, stating that they

“were of the poorest; the rooms were destitute of apparatus or even ordinary school conveniences, whilst to sanitary and hygienic precautions not a thought was given.”

Furthermore, the white girls of the Eighth Ward were given their own school–known as the Garfield School–as they were thought to be too young to travel to white schools outside of the ward. These conditions did not go without notice, fortunately, and the Old Eighth Ward served as an epicenter of educational reform in Harrisburg.

Dr. Rev. William Howard Day worked to integrate Harrisburg’s school system. In 1879, the first African-American students were admitted to the boy’s high school. Two of them, John P. Scott and William Howard Marshall, graduated in 1883. Scott was an especially successful student, and delivered the salutatorian speech at the graduation ceremony. Titled “Stand for Yourself,” Scott, argued that

“the power of self-support is possessed by each individual and upon its use or abuse must each depend for success or failure.”

Moreover, new schools were built in the Eighth Ward, far better suited for educating students. Initially named the Lincoln School, this school was a marked improvement over the cramped Jennings School. Fittingly, one of the first teachers to join the faculty was Harrisburg’s first African-American salutatorian, John Scott. Even more appropriately, when the name “Lincoln” was transferred to a school in Allison Hill, the original Lincoln School was renamed the Day School after William Howard Day. On the other side of the ward, the Wickersham school was dedicated in 1897. Here, Harrisburg’s other first integrated African-American graduate, William Marshall, would serve as principal.

William Howard Day was born in 1825 in New York but was raised by an affluent white family in Northampton, Massachusetts. Before coming to Harrisburg, he obtained a degree at Oberlin College and traveled across the country campaigning for black civil rights. He became the secretary of the National Negro Convention in Cleveland in 1848, partnering with Frederick Douglass to pen the “Address to the Colored People of America.” In 1859, he traveled to the United Kingdom, preaching and working with the YMCA. Upon his return, Day worked for the Freedmen’s Bureau after the Civil War. Day was elected school director in Harrisburg in 1878 and again in 1887. As the first black board member and president, he worked with principal Spencer P. Irvin to integrate three African American students into the Boy’s High School in 1879. While serving as president, he even established Livingstone College with the help of J. C. Price, William H. Goler, and Solomon Porter Hood, a historically black Christian college in Salisbury, North Carolina. Because of his influence, African-American access to secondary education in Pennsylvania significantly increased.

-

Church Communities of the Old Eighth Ward: With Biography of Jacob Compton Website

Olivia Bardo, Zöe Smith, and Rachel Williams

The churches of the Old Eighth Ward were more than just houses of worship. They served as sites of community cohesion, provided primary schooling for many of the ward’s children, and hosted organizers, politicians, and abolitionists.

Wesley Union AME Zion Church was in many ways the heart of the African-American community in the Old Eighth Ward. Originally established in a log cabin at Third and Mulberry streets, the larger brick church at the corner of Tanner Alley and South Street was built in 1839. The Rev. David Stevens grew the early congregation, overseeing an expansion of their property. The Rev. Jacob D. Richardson established a school in the church to meet the needs of the ward’s students. The church continued to grow, requiring new buildings to be built on the same site in 1862 and again in 1894. The church also hosted leading intellectuals and abolitionists, including Frederick Douglass and William Lloyd Garrison. In 1837, the church hosted a meeting of the Anti-Slavery Society as well as the Statewide Convention for Colored Citizens in 1848. Further, the congregation was instrumental in providing refuge to freedom seekers escaping enslavement in the South. Other distinguished members of the congregation included William Howard Day and John P. Scott.

Bethel AME Church was another vibrant African-American congregation in the Old Eighth Ward. The congregation had grown considerably as African-Americans who had earned their emancipation flocked into the Old Eighth Ward. The congregation worked hard to provide housing for the new arrivals and connected them with work opportunities in the local coal, iron, and steel industries. After the passage of the 15th Amendment in 1871, the church also worked hard to register new voters and provide civic education to the ward’s citizens.

Not all migrants into the Old Eighth Ward were African-American. Predominantly Catholic German immigrants also formed the religious fabric of the community. While a Catholic congregation was already established where St. Patrick’s Cathedral stands today, the German population found that they needed instruction in their native language. Thus, St. Lawrence German Catholic church was established. Originally located on Front Street, a larger church was constructed along Walnut Street, dedicated in 1878. Alongside the congregation, members of the Sisters of Christian Charity established a home, taking over teaching duties at the parochial school connected with the congregation.

While he did not live in the Old Eighth Ward, it is also worth noting that a popular hymn-writer, piano and music teacher, and publisher of hymnals, J. H. Kurtzenknabe, an orphaned immigrant from Germany, operated his printing business, Kurtzenknabe Printing for a time at the corner of Short and South Streets. (This corner was the famed “Frisby Battis Corner” that featured prominently in Old Eighth Republican politics.) Kurtzenknabe was most famous for his Sunday School hymnals, many of which were printed in the Old Eighth Ward.

Many other church communities also served the Old Eighth Ward. Second Baptist Church, located just outside the ward along Cameron Street drew many of its congregants from the citizens of the ward. Members of that congregation–many of whom lived either in or near the Old Eighth–left along with its pastor to establish St. Paul Baptist Church, also located on Cameron Street. The First Free Baptist Church was located on the same block as Wesley Union AME Zion

Jacob Compton, the great-grandfather of local musician Jimmy Wood, played an important role in the history of one America’s most beloved presidents; he “spirited Abraham Lincoln out of Harrisburg to evade assassination.” Other than the final attempt that took his life, there were at least five other attempted assassinations of President Abraham Lincoln. One took place even before he took office. In late February of 1861 as he traveled to Washington D.C. from his home in Springfield, Illinois. One of his stops included Harrisburg, and the people of the capital city gathered to see the president-elect. After a flag raising ceremony, city residents went down to Second and Vine Streets, where the train transporting Lincoln and his party arrived around 1:30pm. He was taken to the Jones House hotel in a carriage, and after Governor Curtin introduced him to the crowd of 30,000, from a balcony Lincoln gave “a short speech brimming with patriotism”. Lincoln then gave another patriotic speech to the Pennsylvania State Legislature. After returning to the Jones House, the populace believed he would leave in the morning for Baltimore. However, that evening, Simon Cameron consulted with Curtin and Allan Pinkerton, a Chicago police detective traveling with Lincoln, about a plot to assassinate the president-elect. After hearing of the danger along the planned route, Cameron hastily sent for his personal carriage driver, Jacob Compton, to drive one of the two carriages carrying Lincoln and his fellow travelers. In the night, the carriages were secretly transported to a special train bound first for Philadelphia, then Baltimore, and ultimately to Washington, where he arrived safely. However, while Compton may have had a brush with fame as he guided the future president to safety, he was well-known in Harrisburg as a musician and giving participant in both the Old Eighth Ward and in his church community, Wesley Union A.M.E. Zion church.

-

Making a Home in the Old Eighth Ward: With Biography of Hannah Braxton Jones Website

Mary Culler

According to the 1900 census, just over 50,000 people called Harrisburg their home. Of these 50,000 people, 4,435 lived in the Old Eighth Ward. The eighth ward was disproportionately occupied by African-American residents. A total of 1,507 African Americans lived in the Old Eighth Ward, which comprised about 34% of the population of this ward. This percentage is quite large in comparison to other wards in the city. Second to the eighth ward, the ward with the largest African American population was the second ward; African Americans comprising about 11% of the population. In contrast, the tenth ward was the least diverse, with African Americans comprising only .5% of the total population. The average population percentage of African Americans in all the wards of the city except the Eighth Ward was only about 6%, which is a startling contrast to the 34% of African American residents in the Eighth Ward. The Old Eighth Ward was also home to many immigrants. 359 people, or about 8% of citizens of the Old Eighth Ward were born outside of this county. Also, an additional 359 citizens or 8% had both parents who were born outside of this country, but they themselves were born in the US, mostly in Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia. 859 people had just one parent born outside of this country. Many people of the Old Eighth Ward had strong a strong cultural heritage to another geographic location, which created a uniquely diverse community in the heart of the capital city. Statistically, the Old Eighth Ward was the most diverse neighborhood in the city of Harrisburg, with a high percentage of African American residents and many first or second generation immigrants from all over the world who made their home in the Old Eighth Ward of Harrisburg.

However, this diverse community was greatly affected by the Capitol Park extension. Many people were displaced and forced to relocate to another part of the city, as homes and businesses were torn down to make room for this expanded capitol. About twenty-nine acres, from North Street to Walnut Street were within the land that was taken to extend the capitol complex. Within these twenty nine acres were many homes filled with stories and fond memories of childhood. One story that Wert captures in his article “The Passing of the Old Eighth,” details an encounter between the current and former owner on a house on State Street that was to be demolished. A woman appeared at the door of her former home, and the current owner graciously allowed this woman to tearfully relive her childhood memories in a house that was a home to her years prior. Another story that Wert tells is of a rich man, who earned a lot of money through silver mines, who built his mother a mansion which would have been worth about $10,00 dollars at the time. Wert sought to perpetuate this story of a son’s kindness to his mother by making sure this story was told.

Boarding Houses were also an important lodging in the Old Eighth Ward. However, most boarding houses were seen as a place of vice where alcohol was prominent. Prior to the Capitol Park Extension, Theodore Frye, an African American man, owned a hotel on State Street in the Eighth Ward. In 1913, there were accusations of underage drinking at Frye’s hotel, and by 1917, Frye’s liquor license was rejected, and this was the only liquor license of a person of color in the Old Eighth Ward. Before this in 1916, Frye attempted to move his property in order to protect it from the Capitol Park Extension, but the reputation of “vice” at his boarding house, which was partially influenced by his race, caused opposition to arise from the Pennsylvania Railroad Company. Boarding houses were not only a place with a reputation of vice and liquor. Temperance hotels were founded throughout the Eighth Ward, which were alcohol-free hotels which were intended to be safer for women and children to stay at during their travels. The Women’s Christian Organization was responsible for founding some of these “temperance hotels.” Boarding houses and temperance hotels were an important part of the Old Eighth Ward, and the reputation of boarding houses

Hannah Braxton Jones was born to Joseph and Maria Braxton in Virginia around 1855. When Hannah was about eleven years old, she moved to the Old Eighth Ward of Harrisburg with her family in 1866. After moving to Harrisburg, much of Hannah’s early life revolved around her father’s church, Second Baptist Church, which was founded by Joseph Braxton upon his arrival to Harrisburg. At the time of her father’s death, Second Baptist Church had grown from about six members at its founding to nearly one hundred and seventy five members. In her early twenties, prior to 1880, Hannah married George Jones, and the two remained in Harrisburg and had two children, James and Mary Jones in 1875 and 1878. During this time, Hannah’s husband, George, was a reverend at Second Baptist Church, and Hannah herself was heavily involved in the church through leading women’s Bible studies, performing readings during the service, and contributing to the music. In 1881, George Jones had stepped down as head pastor of Second Baptist Church, but throughout the next ten years, he spoke frequently as a guest speaker. However, by 1900, George Jones had died, leaving Hannah Braxton a widower. Also, during this time Hannah Braxton Jones became one of the few women of color in the city at this time to purchase a house with only her name on the deed. Until her death in 1928, Hanah Jones remained active in her church and in her community, and she taught music in Harrisburg. According to her obituary, Hannah was survived by her two children, six grandchildren, and even two great-grandchildren.

-

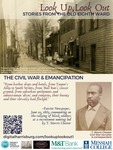

The Civil War and Emancipation: With Biography of T. Morris Chester Website

Mary Culler

Harrisburg was an integral city for the Union during the Civil War. Harrisburg’s canal, roads, and railroads provided an extensive transportation network that connected the state capital of Pennsylvania with the rest of the northern states. Camp Curtin, named after Pennsylvania Governor Andrew Curtin, was founded at the fairgrounds just outside of the city’s northern boundaries at the beginning of the war. As a staging ground for the Union Army, thousands of soldiers passed through the camp between 1861 and 1865 and in turn shaped the small urban center. The influx of soldiers sometimes exceeded the accommodations at Camp Curtin and required use of the grounds of the capitol, while dispute over pay, living arrangements, and food led on several occasions to unrest and rioting in Harrisburg.

Harrisburg was also an important city for the Underground Railroad, both because of its proximity to the Mason-Dixon line and its prime location as a transportation hub. The highest concentration of African-American residents in the city in the second half of the 19th century lived in the neighborhood that would later be identified as the Old Eighth Ward, and Tanner’s Alley, located in the same area, became a center of Underground Railroad activity. Prominent residents of this district, including Edward “King” Bennett and his wife Mary Bennett, Joseph Bustill, and William M. “Pap” Jones and Mary Jones, were all active participants in the Underground Railroad. George and Mary Jane Chester, parents of T. Morris Chester, were born enslaved in Maryland before they liberated themselves and settled in Harrisburg, working tirelessly to assist other freedom seekers. Another resident, Harry Burrs, campaigned for votes for black citizens and was a prominent leader in social clubs and local politics.

Following the war, Harrisburg hosted a “grand review” and parade honoring the members of the United States Colored Troops (USCT). The Garnett League, which was Harrisburg’s chapter of the Pennsylvania State Equal Rights League, was responsible for hosting and planning the event. On the morning of November 14, 1865, the USCT assembled at Camp Curtin and marched to the Capitol, where they were met by both black and white citizens of Harrisburg cheering on the veterans. Although the beloved Governor, Andrew Curtin, was unable to attend due to illness, other prominent citizens such as William Howard Day, T. Morris Chester, and Rev. John Walker Jackson were involved in this celebration. Both General Butler and General Meade spoke very highly of the USCT veterans, and this event marked an important demonstration for the promotion of equal rights.

Thomas Morris Chester, commonly referred to as T. Morris Chester, was an influential individual in Harrisburg’s African-American community during the 1860s. Throughout Chester’s childhood, his parents, who had themselves once been enslaved, assisted freedom seekers in the Underground Railroad in Harrisburg. Chester himself pursued a degree in law and lived abroad in Liberia for a short period before returning to Harrisburg just before the Civil War. During the war, Chester took African Americans to Massachusetts where they could enlist in the United States Colored Troops division of the Union army. Chester also served as the only black war correspondent during the Civil War, working for the Philadelphia Press. After the war ended, Harrisburg hosted a parade celebrating the African-American men who had served in the war. Chester was influential in organizing the parade and served as Grand Marshall in this celebration. In the post-war years, Chester remained a leading and influential member of the black community. In a speech delivered by Chester that was published in the Daily Telegraph, Chester spoke out concerning issues such as the African-American vote and the poor quality schools. Leaving Harrisburg in 1867, Chester completed his master’s degree in England and returned to the States to practice law in Louisiana. He eventually returned to his home city of Harrisburg shortly before his death in 1892.

“From barber shops and hotels, from Tanner’s Alley to South Streets, from ‘Bull Run’s’ classic ground, from suburban settlements and subterranean ‘dives’ and rookeries, their beauty and their chivalry had flocked.” Patriot Newspaper, June 10, 1863, commenting on the rallying of Black soldiers at a recruitment meeting led by T. Morris Chester

-

City Beautiful and the Capitol Extension: With Biography of Dr. William H. Jones Website

Mary Culler and Molly Elspas

At the turn of the century, Harrisburg was at a crossroads. The city was physically deteriorating and had lost its prestige as a thriving steel and railroad center. The rest of America moved on from its industrial boom, and Harrisburg was left behind. Faced with losing its status as a capital city, a change had to be made. Many civic reformers began to speak up about the drastic need for better health conditions in the city. After delivering a rallying speech to the Harrisburg Board of Trade in December 1900, a pivotal local leader, Mira Lloyd Dock ignited an intense reform movement that reinvigorated the city from the inside-out. Within the next thirty years, Harrisburg saw huge renovations in infrastructure, including the construction of a new water filtration system, paved roadways, and many new scenic green spaces. Employing experts like landscape designer Warren H. Manning and engineer James Fuertes, the deteriorating town of Harrisburg developed into a new metropolis.

These structural changes to the city included the Old Eighth Ward. The Old Eighth Ward was not only one of the poorer wards, but also the most diverse wards in the city, populated by many minorities and immigrants. These two aspects of the Eighth Ward’s makeup may have at least partially motivated pervasive newspaper accounts of the Old Eighth as a home to vice. In the wake of the newspaper accounts of the Eighth Ward and in light of the ongoing movement for aesthetically pleasing parks, a 1911 campaign called for an entire section of the Eighth Ward to be razed. In its place, the Capitol Building Park would be extended. Beginning in both 1911 and 1917, the Capitol Park Extension Commission held hearings concerning damage to properties in the Eighth Ward, ultimately condemning and repossessing most properties. In total, 541 properties were taken, and all of their residents were told to relocate. Only 18 owners were actually compensated, while many of the others were victims of foreclosures. Many of the displaced residents migrated to low-cost housing built throughout the city.

Along with individual homeowners, many other buildings in the community of the Eighth Ward were also destroyed and the occupants displaced. Seven business, five churches, two schools, and one hotel were removed from the ward to make way for the Capitol Park Extension. Some of the churches that were uprooted were able to reestablish roots in another part of the Ward. Wesley Union AME, originally located within the limits of the Capitol Park Extension, was able to reestablish elsewhere in the Eighth Ward, but many other churches lost their membership, and were scattered throughout the other wards in the city. Although the purpose of the Capitol Park Extension was to promote the city and further the idea of the “common good,” this movement came at the expense of much of the city’s minority and immigrant populations.

William H. Jones was born in 1860 in Snow Hill, Maryland to William H. and Esther Jones. He remained in this area of Maryland for most of his childhood before moving to Washington, D.C. to study medicine at Howard University for the next three years. Upon leaving Howard, Jones moved to New York to continue his education at the New York Polyclinic Institute as a graduate student. After his graduation in 1887, Jones moved to Knoxville, Tennessee to start his career. He relocated shortly thereafter to Harrisburg and settled in the Old Eighth Ward. Dr. Jones quickly became an active and respected member of the Harrisburg community, esteemed by both African-American residents and white residents of Harrisburg. Jones participated in many committees in Harrisburg, including the local school board and the board of trade, and he was also members of a variety of medical societies throughout the Pennsylvania. As a member of the Board of Trade, Dr. Jones was also involved in the original discussion surrounding the implementation of the City Beautiful movement. However, in 1905, during his active involvement in the community, Dr. Jones slipped and fell on the steps of the capitol and, while he was ill, contracted pneumonia and died about two weeks later. At the time, Dr. Jones was engaged to Margaret Lewis, who was at his side when he died. Because of his prestige in Harrisburg, the Harrisburg Telegraph called his untimely death a “distinct loss to the town” as he was so well respected in his community. Dr. Jones’ funeral was held at his church, St. Paul’s Protestant Episocopal Church. After his death, a memorial association formed in Dr. Jones’ honor. Ten years later, the association built a fountain in remembrance of Jones’ contributions to the city. The fountain was located at a local playground near Twelfth Street.

-

Political Life in the Old Eighth Ward: With Biography of Anna E. Amos Website

Mary Culler and Andrew D. Hermeling

The Old Eighth Ward was a very politically active community. Many citizens were actively involved in a variety of civic organizations to bring about political change in the community. Voting was prominent topic of discussion, especially among black men in the community. Prior to 1838, men of color enjoyed voting privileges in Harrisburg and throughout the state of Pennsylvania, but in 1838, the Pennsylvanian Constitutional Convention disallowed the African American men in Harrisburg the ability to vote. The vote was reinstated for African American men across the country with the passing of the fifteenth amendment in February of 1870. Although by law African American men were able to vote, the amendment did not quell the vehement protests of those who opposed this decision. Despite the opposition, some individuals of the Old Eighth Ward refused to yield their vote. During a voting day in Harrisburg, Major John W. Simpson stood on a store box at a polling place near Umberger’s Cross Keys hotel, and made sure that all people who intended to vote that day were able to place their vote, despite much opposition.

The Old Eighth Ward was also home to a variety of civic organizations. One particular political hub of the Old Eighth is located at the corner of Short and State streets, and is owned by Frisby C. Battis. Not only was this building (pictured above) a polling site, but it also provided a place for many civic organizations to meet. Some of these organizations include State Democratic Colored League, members of the Republican party, J. D. Cameron club, D. H. Hastings club, and many more. Battis himself was a very involved with the Republican party in the city of Harrisburg. Battis not only hosted many of these civic organizations at his residence, but he was also the president of the Cameron Campaign Club. Battis was served multiple terms as an elected official, including a delegate at the Republican convention in Lancaster, and as a doorkeeper at the Republican convention.

Women were also heavily involved in political associations in the Old Eigth Ward. Anne E. Amos is a highly active member of the political community of Harrisburg. She founded the Daughters of Temperance movement, which was one of the organizations through which women were politically involved in Harrisburg . In addition to the Daughters of Temperance, another civic organization, the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, was also heavily involved in the temperance movement in Harrisburg in the early 1900s. Women were also very involved in sparking change outside of work in these civic organizations. During the Great War, over one-hundred women in Harrisburg volunteered and packaged bandages to send to Europe through the Red Cross. The Phillis Wheatley Women’s Christian Temperance Union. also met frequently in the Old Eighth Ward, hosting events for the community. These women’s civic organizations and many more were major contributors to the political landscape of the Old Eighth Ward.

Although records of Anne Amos are scarce, her obituary, written by the groundbreaking Harrisburger J. P. Scott, demonstrates the power of African-American women to effect political change in the Old Eighth Ward. Born at sea to a French mother and a Martiniquan father who passed away three months before her birth, Anne arrived in Pennsylvania when she was six years old. Prior to the Civil War, she and her husband became ardent abolitionists, using their home as a station on the Underground Railroad. Simultaneously, she opened a kindergarten to help provide educational opportunities for African-American children in Harrisburg and continued her educational service in North Carolina during Reconstruction, teaching the newly emancipated.

Upon returning to Harrisburg, Amos founded the Independent Order of Daughters of Temperance. Not only did this organization work to combat alcoholism and vice, but their work was fully intertwined with the women’s suffrage movement. In fact, Amos was so successful in her temperance and suffrage organizing that she was highly sought by white temperance and suffrage advocates as a consultant and advisor. Moreover, her work was also closely tied to her church as well, demonstrating the ways in which politics, reform, and religious life were often closely related.

-

Seeking Shalom in the Old Eighth Ward: With Biographies of Rabbi Dr. Nachman Heller and Rabbi Eliezer Silver Website

Mary Culler and Andrew D. Hermeling

The Old Eighth Ward was the center of Harrisburg’s Litvak–or Lithuanian Jewish–community prior to the Capitol expansion. While an older German Jewish population was already thriving in the city, the newly arriving Litvak found it difficult to integrate with the pre-existing community. Two synagogues were therefore founded in the ward, Kesher Israel and Chisuk Emuna. The presence of both of these congregations serves not only as a testament to the vibrancy of the Jewish community, but also the diversity among these co-religionists.

Chisuk Emuna–originally named “Chiska Emuna bene Russia,” meaning “Strengtheners of Faith of the Children of Russia”–was the first Jewish congregation formed in the Old Eighth Ward by the Litvak fleeing persecution in Russia. These refugees and freedom seekers hailed from just a few towns in Lithuania (which at this time was a part of the Russian empire) and thus were culturally, linguistically, and religiously tight-knit. As such, Chisuk Emuna represented and served a very specific Lithuanian Jewish culture. The congregation was more than a place of worship for Jewish people, it also served to hold the community together as they adjusted to life in a new city where they did not speak the language, eat the same foods, or celebrate the same holidays. Moreover, the synagogue provided culturally appropriate “social security” for its members, as both health and wellness and funerary practices could be difficult to navigate in the community’s new American home.

However, as the Lithuanian Jewish community began to assimilate in Harrisburg, a divide in the Chisuk Emuna congregation emerged. A number of members of the community felt that their Orthodox beliefs were growing more compatible with the larger American culture. Jewish businesses, especially bakers and confectioners in the Old Eighth Ward, had grown to serve more than just the tight-knit Jewish community, helping to enfold them within the larger multi-cultural fabric of Old Eighth. This led to the formation of a new congregation, Kesher Israel, which sought to maintain Orthodox practices while also engaging more with the public. While most members of Chisuk Emuna conducted both their religious and secular business exclusively in Yiddish, Kesher Israel’s congregants were more comfortable with English. This also allowed Kesher Israel to draw congregants from the larger non-Lithuanian Jewish community in Harrisburg.

Joining those who left Chisuk Emuna for Kesher Israel, was Rabbi Eliezer Silver, who left his position of leadership at his former congregation to become the first leader of Kesher Israel. While leading the congregation, Silver became a prominent member of American Rabbinical circles. He used this place of prominence to advocate first for Jewish people suffering in Russia and then, after leaving his position at Kesher Israel, became the first president of Vaad Hatzalah (Rescue Committee) that sought to help Torah scholars escape Nazi-occupied Europe during World War II. It is perhaps no coincidence that a neighborhood that played a prominent role during the American Civil War in assisting freedom seekers would also feature such an important man who worked to save those who may have otherwise died in the Holocaust. Moreover, like those working in the Underground Railroad, Silver was willing to work both within and outside the law to save lives. Even before World War II, he regularly lobbied U.S. presidents to support Jewish people being persecuted in Europe. During the war, he even dressed as a U.S. Army Chaplin and traveled to Europe to gain access to war zones.

Rabbi Silver’s legacy lived on among the Kesher Israel congregation, as he returned in 1933 to help lead the installation service of the congregation’s new rabbi, his son David L. Silver

Rabbi Dr. Nachman Heller only spent a short time in Harrisburg. However, during his time at Kesher Israel Synagogue, he earned a reputation as an important Jewish author, teacher, and intellectual. At a time when anti-Semitism was still rampant, he used his journalistic skill to educate the public about important aspects of Jewish life and worship. For example, he wrote an explanation of the Jewish observances of the Fast of Esther and the Feast of Purim in the Harrisburg Telegraph on March 16, 1908. Similarly, he took great pride in the education of Harrisburg’s Jewish youth, establishing a Hebrew Academy in association with Kesher Israel. Although he left Kesher Israel in 1911 to begin work at another congregation in Charleston, West Virginia, he continued to return to the Old Eighth Ward as a guest lecturer while remaining active as an author and public intellectual.

" burg’s Litvak–or Lithuanian Jewish–community prior to the Capitol expansion. While an older German Jewish population was already thriving in the city, the newly arriving Litvak found it difficult to integrate with the pre-existing community. Two synagogues were therefore founded in the ward, Kesher Israel and Chisuk Emuna. The presence of both of these congregations serves not only as a testament to the vibrancy of the Jewish community, but also the diversity among these co-religionists.

-

Serving the People of the Old Eighth Ward: With Biography of Sister Mary Clare Grace Website

Mary Culler, Andrew D. Hermeling, and Rachel Williams

While many of Harrisburg’s City Beautiful advocates sought to “save” the people of the Old Eighth Ward from the outside, many individuals and organizations within the ward dedicated their lives to serving the community as well as the wider city. The Old Eighth Ward was home to a number of fraternal and sororal organizations dedicated to community service. The largest and oldest of these organizations was the Grand United Order of Odd Fellows, which met at the Brotherly Love Lodge located right next to the famed “Frisby Battis Corner,” the center of African-American Republican politics in the ward. Among the members of the G.U.O.O.F were famed Harrisburgers Jacob Compton, Joseph L. Thomas, and Colonel Strothers. Simultaneously, many of the women of the ward, such as Martha F. Saunders and Anna E. Amos, were members of the Daughters of Temperance. Not only did these organizations provide social security and stability to a community before the New Deal, they also had a long history of working for emancipation and African-American rights prior to the Civil War. In fact, in a time when southern states still enslaved African-Americans, both organizations led August 1st Emancipation Day parades which celebrated the abolition of slavery in British Caribbean colonies–a precursor to Juneteenth celebrations of the Emancipation Proclamation in the United States. As an organization named “Daughters of Temperance” would indicate, this was indeed a time when many institutions were also concerned with combatting drunkenness and alcohol consumption. The Old Eighth Ward was the site of many hotels and saloons that served alcohol–including many that continued to serve alcohol during Prohibition–that largely catered to traveling canal and rail workers, soldiers stationed in the city, as well as others who did not live in the ward. This led to the rise of “Temperance Hotels,” which sought to serve these travelers while also encouraging sobriety. Ironically, one such hotel was demolished long before Capitol expansion in order to make space for expansions of the Pennsylvania Rail Road. Later, the Daughters of Temperance opened a Temperance Hall that served as the headquarters for both their social reform efforts as well as women’s suffrage advocacy. One other prominent organization working for temperance was the Keeley Institute, which was housed in the largest mansion in the ward, the James Russ House. Before the rise of the 12-step method for treating addiction, the Keeley Cure was literally the “gold standard,” as central to the treatment was the injection of bichloride of gold. While we now know that this is a dangerous medical treatment, the Keeley method also focused on treating addicts in caring, home-like environments, making the Russ House the perfect site for the institute. For a short time, the Keeley Institute relocated, and during that time, the Russ House served as the St. Clare Infirmary run by Sister Mary Clare Grace and the Sisters of Mercy in Harrisburg. As this was a time of virulent anti-Catholicism in America, the reputation and adoration that Sister Mary Clare Grace received is all the more remarkable. The St. Clare Infirmary was open during the Spanish-American War and many soldiers from nearby Camp Meade were treated there. Finally, as a neighborhood with many wooden structures, fire companies were crucial for maintaining the safety for the ward’s residents. The first company, the Citizens Fire Company was chartered in 1841, and the ward was always very proud of its service record. The second department, the Mt. Vernon Company was founded in 1858, and the leadership of the company was an important civic stepping stone for notable Harrisburgers. Sister Mary Clare Grace was born in Ireland in 1833 and trained as a sister at St. Xavier Academy in Chicago. She arrived in Harrisburg on September 1, 1869. Even though she was born into a relatively affluent family, she immediately earned a reputation in Harrisburg for living a life of Holy poverty. She was also known for strict observance of religious discipline. However, this strictness made her an incredibly effective institutional leader, whether she was running St. Genevieve’s Academy, the Mercy Home residence for other Sisters of Mercy, or the St. Clare’s Infirmary. When she arrived in Harrisburg, she was often met publicly with anti-Catholic sneers, a common experience for Sisters in conspicuous habits across the United States in the nineteenth century. However, by the time she passed in 1911, having lived in retirement in the very St. Genevieve’s Academy, the people of Harrisburg flocked to her funeral and sang the praises of her life of service.

-

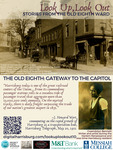

The Old Eighth: Gateway to the Capitol: With Biography of Gwendolynn Bennett Website

Molly Elspas and Andrew D. Hermeling

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, Harrisburg began to develop as an industrial center. Railroad steel, cigars, flour, shoes, and many other businesses thrived, especially in the Eighth Ward. A large thoroughfare was required in order to accommodate the movement of raw materials throughout the city for processing. Like most industrial societies, Harrisburg utilized water as a means of transportation, with the Susquehanna River flowing alongside the southern border of the city. The Harrisburg canal system was started in a similar manner as the City Beautiful movement– through internal efforts. In 1822, the Harrisburg Canal, Fire Insurance and Water Company was formed by a group of local businessmen to build a canal “from John Carson’s property near Second mountain to Harrisburg and through Paxton creek valley…to the north, possibly Mulberry street.” The original people behind the canal system had grandiose ideas for its industrial capabilities in the city, with images of mills lining the waterways for miles. However, the State “got into the canal business” and interrupted the company’s plan by taking over the land that the canals were being built. Despite this change of ownership, the canals were officially built in 1826, along many lines of “interesting enterprise.”

These canals served as gateways for economic prosperity in Harrisburg, bringing increasing business to the Old Eighth Ward. Roads were built along the canals out of necessity in order to accommodate foot traffic from the canals. With the canals increasing the amount of products that could be introduced into the city, a better system of land transportation was needed. Beginning in the 1830s, rail lines were being installed throughout the city to connect with the canals. By 1834, there was a complete line of transportation between Philadelphia and Pittsburgh, with Harrisburg serving as a natural midpoint. Due to the increasing railway lines being built, additional lines began to connect through Harrisburg until it became one of the leading railroad centers in the United States. With most of these lines running to or around the factories of the Old Eighth Ward, it became known as a stopping place frequented by all walks of life.

Harrisburg, according to historian J. Howard Wert, “was a radiating point for the distribution of goods north, south, east, and west. This same law of location made it an inevitable railroad center.” Comprised of many factories, schools, churches, and small businesses, the Eighth Ward acted as a gateway to the rest of the city, prospering from the constant influx of people from the railway lines. Blue collar workers who traveled along with canal industry frequented many of the ward’s institutions. Union soldiers encamped at Camp Curtain would often find their way to the speakeasies to engage in games. In this way, the Old 8th Ward was a hub for people from many different walks of life.

The canals and railroads that passed through and around the Old 8th brought people from across the country into the city. They connected Pennsylvania’s capital city to the rest of America. Many people’s first introduction to Harrisburg was stepping off the trains in the Eighth Ward, experiencing the diverse life that it fostered. These transportation networks fostered opportunity for work, trade, and interaction between a variety of people, bringing even greater life to the ward and the city as a whole.

Gwendolyn Bennett would come to be world-renowned as one of the many writers and artists who were collectively part of the African-American cultural flourishing of the 1920s known as the Harlem Renaissance. However, before making her way to Manhattan Island, Gwendolyn Bennett spent time in Harrisburg. Unfortunately, she did not arrive under the best of circumstances, as she was kidnapped by her own father and stepmother amidst a custody dispute. Because Harrisburg was such a busy transportation hub at the time, Bennett’s father was able to avoid authorities until they relocated to Brooklyn in 1918. However, despite the troubling circumstances of Bennett’s time in Harrisburg, she nevertheless flourished in her elementary school, attending the Lincoln School located in the Old Eighth Ward.

-

Vice and Virtue in the Old Eighth: With Biography of Joseph L. Thomas Website

Molly Elspas, Andrew D. Hermeling, and Rachel Williams

One of the most exhaustive resources for studying the Old Eighth Ward is a series of columns published in the Patriot newspaper between 1912 and 1913 penned by local educator and editorialist, J. Howard Wert, titled “Passing of the Old Eighth.” A white Civil War veteran, he was politically progressive for the time, and while he was active in the Harrisburg school system, he was a strident advocate for school integration, often partnering with the African-American educational reformer, William Howard Day. However, Wert was also a staunch advocate for the Capitol expansion project and the City Beautiful movement and believed that on the whole, the Old Eighth Ward was a neighborhood marked by vice and ultimately a blight upon Harrisburg’s civic landscape.

Thus, when Wert sought to “tell the story” of the Old Eighth, he did so from a very particular vantage point. His progressivism was marked by the kind of white paternalism that was all-too-common at the time. In their edited collection of Wert’s columns, historians Michael Barton and Jessica Dorman note that Wert was at his most descriptive when describing the vice of the city. Describing the actions of canal workers who frequented the ward’s drinking establishments, Wert wrote that

There were orgies by day, and fiercer orgies by night that were protracted till the stars had paled before the brightening eastern skies. J. Howard Wert, “Passing of the Old Eighth,” Patriot, February 17, 1913.

Two drinking establishments, Lafayette Hall and the Red Lion, were especially prominent in both Wert’s descriptions of the Old Eighth Ward as well as the perception by Harrisburg’s more affluent public. Although Lafayette Hall was intended to be a well-appointed and garish restaurant, bar, and dance hall, it’s owner, Harry Cook–whom Wert describes as quite the villain–could not obtain the proper licenses for operating the establishment. But that did not stop Cook, and Lafayette Hall became an infamous yet ostentatious destination for heavy drinking and other carousing. At the other end of the spectrum yet no less notorious was the Red Lion. As Wert writes

“if a Harrisburger wanted to show a visiting sport from another city a gilded palace of sin, he took him to Lafayette Hall. But if he wanted to show the same visitor sin itself in concetrated form, without any ornamentation, flounces, or furbelows, he took him to the ‘Red Lion,’ and the visitor generally came away admitting that the Five Points of New York, or the Old Loun in Baltimore had nothing to beat it.” J. Howard Wert, “Passing of the Old Eighth,” Patriot, June 23, 1913.

However, it is important to note that while the Old Eighth Ward might have been the location of these “dens of iniquity,” the majority of their clientele were not residents of the neighborhood. Most patrons searching out hard liquor, illegal gambling, and even prostitution were those who did not even call the city home. During the Civil War, soldiers stationed at nearby Camp Curtin poured into the Old Eighth. So too did canal and rail workers with their wages burning holes in their pockets. Yet this detail was lost on most civic reformers from outside the ward. The railroad was the lifeblood of Harrisburg industry, so it was easier to displace some of Harrisburg’s poorer residents in the name of public health and virtue than try and regulate the industries that supported the ward’s illicit economy.

At the same time, Wert knew enough about the residents of the ward that he felt he needed to offer a counterweight to his persistent descriptions of vice. In a column dedicated to both an addiction treatment center and a hospital that had existed in the Old Eighth, Wert wrote

“To prevent any misapprehension, I wish to say again, most emphatically, that, althought disgraceful vice conditions were in evidence, year after year, in the ‘Old Eighth,’ yet it has it always been the home of many devoted and noble men and women whose unsullied lives shine all the more brightly by the contrast.” J. Howard Wert, “Passing of the Old Eighth,” Patriot, May 12, 1913

It is also worth noting that in close proximity to the vice of the ward were vibrant religious communities–both Christian and Jewish–as well as an extremely popular temperance movement. One of the most prominent temperance organizations were the Daughters of Temperance, who not only worked to combat alcohol consumption but were instrumental in advocating for emancipation prior to the Civil War and Women’s suffrage.

The story of one individual of a downtrodden and oppressed race upon whose patient endurance of the vessels of injustice have discharged their contents for centuries… possessed of indomitable resolution, tireless energy and rectitude of purpose… one of the best known citizens of Harrisburg, respected by all Harrisburg Telegraph, May 20, 1911.

Joseph L. Thomas stands in sharp contrast to the colorful villains that populated Wert’s columns. In fact, it is quite notable and perhaps evidence of Wert’s myopic perspective that Thomas never appeared in the “Passing of the Old Eighth” series, despite being one of the most well-known, respected, and beloved residents, business owners, and civic leaders from the ward. Thomas was born in Winchester, Virginia in 1852, but by 1911 he was a Harrisburg resident for over fifty years and had his home and office at 429 State Street in the Old Eighth Ward. In fact, his residence was located directly under the current Pennsylvania War Veterans’ Memorial Fountain of Capitol Park. In 1895, he joined the undertaking business with a partner who soon after died, and Harriet A. Hill, the partner’s widow, turned over the business to Thomas. As a graduate of four of the leading embalming schools in the country, and rising above being orphaned as a teenager, the citizens of Harrisburg had great respect for his excellence in his position. The citizens of Harrisburg also elected him to the city’s Common Council for two terms and to the School Board for one term. He was also a prominent member of Harrisburg’s fraternal organizations, rising to the position of chairman of the Masonic Grand Lodge of Pennsylvania, whose mission concerned taking care that no family should be wanting or lacking support when facing affliction.

Thomas was so beloved in Harrisburg that in 1911, just as the state legislature was passing the Capitol expansion bill, the Harrisburg Telegraph published a glowing full-length column praising the African-American leader. Drawing comparisons to none other than Frederick Douglass and Booker T. Robinson, the column urged people to

“There are men in every community, less known to fame than they, who, unostentatiously, are laboring in the same vineyard, doing the work the Master gives them to do. Harrisburg has such workers and one of the number is Joseph L. Thomas”

-

Great Speakers of the Old Eighth Ward: With Biography of Frances Harper Website

Molly Elspas and Rachel Williams

The Old Eighth Ward was one of Harrisburg’s most diverse neighborhoods in the later 19th and early 20th centuries. The district’s varied ethnic and racial composition was unparalleled elsewhere in the city, and its residents were engaged in a range of occupations. Many were run-of-the-mill laborers who found employment in the nearby railroads and manufacturing facilities. Others represented a variety of professional classes: small business owners, lawyers, preachers, nurses, and teachers, among others. From the period before the Civil War to the opening years of the 20th century, the Old Eighth hosted numerous social events including public speeches from influential reformers and intellectuals. Public talks, sponsored by local clubs and civic associations, were common at venues such as the Lochiel and Brant hotels, while the churches, synagogues, and squares of the ward also hosted countless speakers—both local and national—who inspired change.

One of the most famous speakers to come to the Old 8th Ward was abolitionist Frederick Douglass. He traveled to the city of Harrisburg multiple times between 1846 and 1895. According to the Harrisburg Telegraph, in 1895, he first came as,

a young man who was active in trying to secure the liberation of his race from bondage.

Douglass spoke on a number of topics, drawing together Republicans from all over the city. He called for “the extension of the elective franchise to the colored people…” Douglass also came to many of the historically African American churches including the Wesley Union A.M.E. and Bethel A.M.E. congregations and well received by the whole ward.

Other speakers such as W. Justin Carter and A. Dennee Bibb spoke in the late 19th and early 20th century about Douglass and tried to further his mission. Others such as Francis Harper came to advocate for women’s rights. At a meeting of the National Council of Women in 1891, she stated:

There are some rights more precious than the rights of property or the claims of superior intelligence: they are the rights of life and liberty, and to these the poorest and humblest man has just as much right as the richest and most influential man in the country.

Frances Harper was a prolific anti-slavery poet and speaker who advocated for women’s suffrage and temperance as well as abolition. Born in 1825 in Maryland, she became an orphan at three years of age and went to live with her uncle, William Watkins, a teacher at the Academy for Negro Youth and a radical political figure in civil rights; his activism influenced Harper’s political, religious, and social views. Harper began publishing her writing at a young age, her first book being released when she was 20 years old. She wrote many additional literary works over the course of her life. In 1850, she became the first woman to teach at Union Seminary in Wilberforce, Ohio, with the support of Reverend John Brown, and later she taught in Pennsylvania and participated in the Underground Railroad. She began her activism through anti-slavery speeches in 1854 as a representative of the State Anti-Slavery Society of Maine, and donated much of the profits from the sales of her books toward abolitionist causes. She made many visits to Harrisburg to give speeches, including several on the topic of temperance. On February 10th of 1883 and February 21st of 1889, she led temperance meetings at the Short Street A. M. E. Church. She also directed a temperance meeting at the Wesley Union Church on South Street in October of 1884. Harper continued her work as both a writer and speaker on social issues social involvement until her death in 1911. A Harrisburg newspaper reported that she “had done more for her race than any other woman.” She undoubtedly left a lasting impression on the people and church communities of the Old Eighth Ward.

-

Business and Social Life in the Old Eighth Ward: With Biography of Colonel W. Strothers Website

Andrew D. Hermeling and Rachel Williams

Despite its reputation as a lower-income and vice-ridden region, the Old Eighth Ward was a thriving place for businesses, both large and small. In fact, much of the neighborhood’s reputation for unhealthiness was a result of the prominent industries that called the ward home. One such factory was W. O. Hickok Manufacturing Company, also referred to as the “Eagle Works,” the oldest and most prominent industrial plant in the Old Eighth Ward and one of the first manufacturing plants to use electricity for light and power. Additionally, Eagle Works’ founder, Orvil Hickok, served as a councilman for the borough of Harrisburg.Gordon Manufacturing Company, located at 424 and 426 State Street, was another hub of manufacturing within the Old Eighth Ward. After starting in the attic of a dwelling on South Fourteenth Street in 1898, it moved to a large brick building on Montgomery Street, and then to State Street due to the company’s continuing growth.

Right next door to the Gordon Manufacturing Company was the Paxton Flour and Feed Company, organized in 1872 by John Hoffer, Levi Brandt, and the James McCormick estate. The feed company was one of the leading grain shipping centers of Central Pennsylvania with multiple locations throughout Cumberland County.Kurtzenknabe Printing was owned and operated by the family notable musician, hymn-writer, and teacher, J. H. Kurtzenknabe. Kurtzenknabe used the print shop to publish a number of successful hymnals, many designed specifically for children.Not all business in the Old Eighth Ward was industrial. Printing offices, pool houses, drug stores, bakeries, confectioneries, restaurants, and laundry services also thrived. The ownership of these small businesses reflected the diversity of the Old Eighth Ward community. German bakers, for example, became prominent, serving the entire neighborhood. One such baker was Frederick Wagner, who emigrated from Prussia in 1855. He operated a bakery at the corner of State and Cowden Streets for forty-four years, employing a number of apprentices, thus growing the profession as he succeeded. Lewis Silbert, a member of the Jewish community operated a confectionery just down the street from Wagner as well as a cigar store. Besides his family, fourteen others lived and worked with him, which included four African-Americans who had emigrated from the South as well as four mixed-race individuals.Business and politicsoften mixed in the Old Eighth. In fact, one block of businesses became the heart of African-American Republican politics at the time. The corner of Short and South Streets came to be known as “Frisby Battis Corner.” Frisby C. Battis lived there and operated a saloon, a cigar store, and a pawn shop from the building. Next door he opened a pool room which became a headquarters for Republican politics in the Old Eighth Ward, especially as Battis sought to challenge the powerful Democratic Alderman Charles P. Walter. In fact, Battis once found himself in front of a judge as a result of this potent mixture of business and politics. Accused of selling liquor on a Sunday as well as operating a gambling house, the charges were contested with arguments that Battis was being persecuted for his political work by over-zealous Democrats. Although the judge threw out the case, Battis took this as a sign and relocated to Washington D.C. While Republican allies swore that Battis was being unfairly harassed, it is worth noting that despite his partisan allegiances, his place of business and home was used as a poling place for one precinct of the Old Eighth Ward, leading to many accusations of election interference. Regardless, up until the demolition of the Old Eighth Ward, “Frisby Battis Corner” was regularly listed in papers advertising polling places for residents of the ward.“Among the local industries that distinguish Harrisburg as a manufacturing city is one that has carried its good name far and wide…. This industry has grown wonderfully during the past few years and on the factories known most widely throughout this and other countries is the Gordon Manufacturing Company.” Harrisburg Daily Independent, October 2, 1905

Many other businesses and social institutions called “Frisby Battis Corner” home. Colonel W. Strothers operated a pool hall which shared the property with the Brotherly Love Lodge, the Harrisburg headquarters for the oldest and most active African-American Fraternal organization of the time, the Grand United Order of Odd Fellows. Strothers was similarly involved in local politics and social welfare organizations. So too was William Parson’s, who owned a drug store across the street from Battis’s businesses.

Colonel W. Strothers was a larger-than-life personality in the Old Eighth Ward. He owned a number of different business, including a pool hall, restaurant, cigar store, and barbershop, most of which were located next to his home in the Old Eighth Ward. Despite being over 300 pounds, he also earned a reputation for being an excellent dancer, even providing dance lessons throughout Harrisburg. However, he is perhaps best remembered as the manager of the Harrisburg Giants, which at the time played in the Eastern Colored League, earning a reputation for a high-powered offense.

While the Harrisburg Giants’ success came after the demolition of the Old Eighth, Strothers’s ability to raise and run the team was deeply tied to his life there. Originally a police officer, he quickly transitioned to business and politics. Like many of the Old Eighth’s African-American leaders, he was prominent within fraternal organizations, active in the church community, and like his close colleague Frisby Battis, used his businesses to host and promote Republican politics in the ward.

-

Civil War & Emancipation - With biography of T. Morris Chester

Digital Harrisburg and Andrew Dyrli Hermeling

Harrisburg was an integral city for the Union during the Civil War. Harrisburg’s canal, roads, and railroads provided an extensive transportation network that connected the state capital of Pennsylvania with the rest of the northern states. Camp Curtin, named after Pennsylvania Governor Andrew Curtin, was founded at the fairgrounds just outside of the city’s northern boundaries at the beginning of the war. As a staging ground for the Union Army, thousands of soldiers passed through the camp between 1861 and 1865 and in turn shaped the small urban center. The influx of soldiers sometimes exceeded the accommodations at Camp Curtin and required use of the grounds of the capitol, while dispute over pay, living arrangements, and food led on several occasions to unrest and rioting in Harrisburg.

Harrisburg was also an important city for the Underground Railroad, both because of its proximity to the Mason-Dixon line and its prime location as a transportation hub. The highest concentration of African-American residents in the city in the second half of the 19th century lived in the neighborhood that would later be identified as the Old Eighth Ward, and Tanner’s Alley, located in the same area, became a center of Underground Railroad activity. Prominent residents of this district, including Edward “King” Bennett and his wife Mary Bennett, Joseph Bustill, and William M. “Pap” Jones and Mary Jones, were all active participants in the Underground Railroad. George and Mary Jane Chester, parents of T. Morris Chester, were born enslaved in Maryland before they liberated themselves and settled in Harrisburg, working tirelessly to assist other freedom seekers. Another resident, Harry Burrs, campaigned for votes for black citizens and was a prominent leader in social clubs and local politics.

Following the war, Harrisburg hosted a “grand review” and parade honoring the members of the United States Colored Troops (USCT). The Garnett League, which was Harrisburg’s chapter of the Pennsylvania State Equal Rights League, was responsible for hosting and planning the event. On the morning of November 14, 1865, the USCT assembled at Camp Curtin and marched to the Capitol, where they were met by both black and white citizens of Harrisburg cheering on the veterans. Although the beloved Governor, Andrew Curtin, was unable to attend due to illness, other prominent citizens such as William Howard Day, T. Morris Chester, and Rev. John Walker Jackson were involved in this celebration. Both General Butler and General Meade spoke very highly of the USCT veterans, and this event marked an important demonstration for the promotion of equal rights.

T. Morris Chester

Thomas Morris Chester, commonly referred to as T. Morris Chester, was an influential individual in Harrisburg’s African-American community during the 1860s. Throughout Chester’s childhood, his parents, who had themselves once been enslaved, assisted freedom seekers in the Underground Railroad in Harrisburg. Chester himself pursued a degree in law and lived abroad in Liberia for a short period before returning to Harrisburg just before the Civil War. During the war, Chester took African Americans to Massachusetts where they could enlist in the United States Colored Troops division of the Union army. Chester also served as the only black war correspondent during the Civil War, working for the Philadelphia Press. After the war ended, Harrisburg hosted a parade celebrating the African-American men who had served in the war. Chester was influential in organizing the parade and served as Grand Marshall in this celebration. In the post-war years, Chester remained a leading and influential member of the black community. In a speech delivered by Chester that was published in the Daily Telegraph, Chester spoke out concerning issues such as the African-American vote and the poor quality schools. Leaving Harrisburg in 1867, Chester completed his master’s degree in England and returned to the States to practice law in Louisiana. He eventually returned to his home city of Harrisburg shortly before his death in 1892.

“From barber shops and hotels, from Tanner’s Alley to South Streets, from ‘Bull Run’s’ classic ground, from suburban settlements and subterranean ‘dives’ and rookeries, their beauty and their chivalry had flocked.” Patriot Newspaper, June 10, 1863, commenting on the rallying of Black soldiers at a recruitment meeting led by T. Morris Chester

-

Great Speakers of the Old Eighth Ward - With biography of Frances Harper

Digital Harrisburg and Andrew Dyrli Hermeling

The Old Eighth Ward was one of Harrisburg’s most diverse neighborhoods in the later 19th and early 20th centuries. The district’s varied ethnic and racial composition was unparalleled elsewhere in the city, and its residents were engaged in a range of occupations. Many were run-of-the-mill laborers who found employment in the nearby railroads and manufacturing facilities. Others represented a variety of professional classes: small business owners, lawyers, preachers, nurses, and teachers, among others. From the period before the Civil War to the opening years of the 20th century, the Old Eighth hosted numerous social events including public speeches from influential reformers and intellectuals. Public talks, sponsored by local clubs and civic associations, were common at venues such as the Lochiel and Brant hotels, while the churches, synagogues, and squares of the ward also hosted countless speakers—both local and national—who inspired change.

One of the most famous speakers to come to the Old 8th Ward was abolitionist Frederick Douglass. He traveled to the city of Harrisburg multiple times between 1846 and 1895. According to the Harrisburg Telegraph, in 1895, he first came as,

a young man who was active in trying to secure the liberation of his race from bondage.

Douglass spoke on a number of topics, drawing together Republicans from all over the city. He called for “the extension of the elective franchise to the colored people…” Douglass also came to many of the historically African American churches including the Wesley Union A.M.E. and Bethel A.M.E. congregations and well received by the whole ward.

Other speakers such as W. Justin Carter and A. Dennee Bibb spoke in the late 19th and early 20th century about Douglass and tried to further his mission. Others such as Francis Harper came to advocate for women’s rights. At a meeting of the National Council of Women in 1891, she stated:

There are some rights more precious than the rights of property or the claims of superior intelligence: they are the rights of life and liberty, and to these the poorest and humblest man has just as much right as the richest and most influential man in the country.

Frances Harper was a prolific anti-slavery poet and speaker who advocated for women’s suffrage and temperance as well as abolition. Born in 1825 in Maryland, she became an orphan at three years of age and went to live with her uncle, William Watkins, a teacher at the Academy for Negro Youth and a radical political figure in civil rights; his activism influenced Harper’s political, religious, and social views. Harper began publishing her writing at a young age, her first book being released when she was 20 years old. She wrote many additional literary works over the course of her life. In 1850, she became the first woman to teach at Union Seminary in Wilberforce, Ohio, with the support of Reverend John Brown, and later she taught in Pennsylvania and participated in the Underground Railroad. She began her activism through anti-slavery speeches in 1854 as a representative of the State Anti-Slavery Society of Maine, and donated much of the profits from the sales of her books toward abolitionist causes. She made many visits to Harrisburg to give speeches, including several on the topic of temperance. On February 10th of 1883 and February 21st of 1889, she led temperance meetings at the Short Street A. M. E. Church. She also directed a temperance meeting at the Wesley Union Church on South Street in October of 1884. Harper continued her work as both a writer and speaker on social issues social involvement until her death in 1911. A Harrisburg newspaper reported that she “had done more for her race than any other woman.” She undoubtedly left a lasting impression on the people and church communities of the Old Eighth Ward.

-

Vice and Virtue of the Old Eighth Ward - With Biography of Joseph L. Thomas

Digital Harrisburg and Andrew Dyrli Hermeling

One of the most exhaustive resources for studying the Old Eighth Ward is a series of columns published in the Patriot newspaper between 1912 and 1913 penned by local educator and editorialist, J. Howard Wert, titled “Passing of the Old Eighth.” A white Civil War veteran, he was politically progressive for the time, and while he was active in the Harrisburg school system, he was a strident advocate for school integration, often partnering with the African-American educational reformer, William Howard Day. However, Wert was also a staunch advocate for the Capitol expansion project and the City Beautiful movement and believed that on the whole, the Old Eighth Ward was a neighborhood marked by vice and ultimately a blight upon Harrisburg’s civic landscape.

Thus, when Wert sought to “tell the story” of the Old Eighth, he did so from a very particular vantage point. His progressivism was marked by the kind of white paternalism that was all-too-common at the time. In their edited collection of Wert’s columns, historians Michael Barton and Jessica Dorman note that Wert was at his most descriptive when describing the vice of the city. Describing the actions of canal workers who frequented the ward’s drinking establishments, Wert wrote that

There were orgies by day, and fiercer orgies by night that were protracted till the stars had paled before the brightening eastern skies. J. Howard Wert, “Passing of the Old Eighth,” Patriot, February 17, 1913.

Two drinking establishments, Lafayette Hall and the Red Lion, were especially prominent in both Wert’s descriptions of the Old Eighth Ward as well as the perception by Harrisburg’s more affluent public. Although Lafayette Hall was intended to be a well-appointed and garish restaurant, bar, and dance hall, it’s owner, Harry Cook–whom Wert describes as quite the villain–could not obtain the proper licenses for operating the establishment. But that did not stop Cook, and Lafayette Hall became an infamous yet ostentatious destination for heavy drinking and other carousing. At the other end of the spectrum yet no less notorious was the Red Lion. As Wert writes

“if a Harrisburger wanted to show a visiting sport from another city a gilded palace of sin, he took him to Lafayette Hall. But if he wanted to show the same visitor sin itself in concetrated form, without any ornamentation, flounces, or furbelows, he took him to the ‘Red Lion,’ and the visitor generally came away admitting that the Five Points of New York, or the Old Loun in Baltimore had nothing to beat it.” J. Howard Wert, “Passing of the Old Eighth,” Patriot, June 23, 1913.

However, it is important to note that while the Old Eighth Ward might have been the location of these “dens of iniquity,” the majority of their clientele were not residents of the neighborhood. Most patrons searching out hard liquor, illegal gambling, and even prostitution were those who did not even call the city home. During the Civil War, soldiers stationed at nearby Camp Curtin poured into the Old Eighth. So too did canal and rail workers with their wages burning holes in their pockets. Yet this detail was lost on most civic reformers from outside the ward. The railroad was the lifeblood of Harrisburg industry, so it was easier to displace some of Harrisburg’s poorer residents in the name of public health and virtue than try and regulate the industries that supported the ward’s illicit economy.

At the same time, Wert knew enough about the residents of the ward that he felt he needed to offer a counterweight to his persistent descriptions of vice. In a column dedicated to both an addiction treatment center and a hospital that had existed in the Old Eighth, Wert wrote

“To prevent any misapprehension, I wish to say again, most emphatically, that, althought disgraceful vice conditions were in evidence, year after year, in the ‘Old Eighth,’ yet it has it always been the home of many devoted and noble men and women whose unsullied lives shine all the more brightly by the contrast.” J. Howard Wert, “Passing of the Old Eighth,” Patriot, May 12, 1913

It is also worth noting that in close proximity to the vice of the ward were vibrant religious communities–both Christian and Jewish–as well as an extremely popular temperance movement. One of the most prominent temperance organizations were the Daughters of Temperance, who not only worked to combat alcohol consumption but were instrumental in advocating for emancipation prior to the Civil War and Women’s suffrage.

The story of one individual of a downtrodden and oppressed race upon whose patient endurance of the vessels of injustice have discharged their contents for centuries… possessed of indomitable resolution, tireless energy and rectitude of purpose… one of the best known citizens of Harrisburg, respected by all Harrisburg Telegraph, May 20, 1911.

Joseph L. Thomas stands in sharp contrast to the colorful villains that populated Wert’s columns. In fact, it is quite notable and perhaps evidence of Wert’s myopic perspective that Thomas never appeared in the “Passing of the Old Eighth” series, despite being one of the most well-known, respected, and beloved residents, business owners, and civic leaders from the ward. Thomas was born in Winchester, Virginia in 1852, but by 1911 he was a Harrisburg resident for over fifty years and had his home and office at 429 State Street in the Old Eighth Ward. In fact, his residence was located directly under the current Pennsylvania War Veterans’ Memorial Fountain of Capitol Park. In 1895, he joined the undertaking business with a partner who soon after died, and Harriet A. Hill, the partner’s widow, turned over the business to Thomas. As a graduate of four of the leading embalming schools in the country, and rising above being orphaned as a teenager, the citizens of Harrisburg had great respect for his excellence in his position. The citizens of Harrisburg also elected him to the city’s Common Council for two terms and to the School Board for one term. He was also a prominent member of Harrisburg’s fraternal organizations, rising to the position of chairman of the Masonic Grand Lodge of Pennsylvania, whose mission concerned taking care that no family should be wanting or lacking support when facing affliction.

Thomas was so beloved in Harrisburg that in 1911, just as the state legislature was passing the Capitol expansion bill, the Harrisburg Telegraph published a glowing full-length column praising the African-American leader. Drawing comparisons to none other than Frederick Douglass and Booker T. Robinson, the column urged people to

“There are men in every community, less known to fame than they, who, unostentatiously, are laboring in the same vineyard, doing the work the Master gives them to do. Harrisburg has such workers and one of the number is Joseph L. Thomas”

-

Business and Social Life in the Old Eighth Ward - With biography of Colonel W. Strothers

Andrew Dyrli Hermeling and Digital Harrisburg

Despite its reputation as a lower-income and vice-ridden region, the Old Eighth Ward was a thriving place for businesses, both large and small. In fact, much of the neighborhood’s reputation for unhealthiness was a result of the prominent industries that called the ward home.

One such factory was W. O. Hickok Manufacturing Company, also referred to as the “Eagle Works,” the oldest and most prominent industrial plant in the Old Eighth Ward and one of the first manufacturing plants to use electricity for light and power. Additionally, Eagle Works’ founder, Orvil Hickok, served as a councilman for the borough of Harrisburg.Gordon Manufacturing Company, located at 424 and 426 State Street, was another hub of manufacturing within the Old Eighth Ward. After starting in the attic of a dwelling on South Fourteenth Street in 1898, it moved to a large brick building on Montgomery Street, and then to State Street due to the company’s continuing growth.

“Among the local industries that distinguish Harrisburg as a manufacturing city is one that has carried its good name far and wide…. This industry has grown wonderfully during the past few years and on the factories known most widely throughout this and other countries is the Gordon Manufacturing Company.” Harrisburg Daily Independent, October 2, 1905